The African elephant is extremely intelligent, highly adaptable, and exhibits remarkable social cohesion. This species is also the IUCN Species of the Day and is ranked by the EDGE of Existence programme as the 77th most important mammal for conservation because it is both unusual and threatened.

The African elephant (Loxodonta africana) and the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) are the only elephant species remaining from a formerly diverse evolutionary radiation. A third species in this taxonomic group, the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius), survived into early historical times. This group is thought to have originated in Africa during the Eocene (50-60 million years ago), when the Earth was a very different place. For example, the temperature gradient from equator to pole was only half that of today’s – temperate forests extended right to the poles, which were much warmer than they are today – and at this time India began its collision with Asia, which caused the Himalayas to fold into existence. From Africa, the elephant group spread to Europe, Asia, and North and South America.

The African elephant is believed to be the more primitive of the two surviving elephant species, which are so unusual that their closest living relatives are the sea cows (manatees and dugongs).

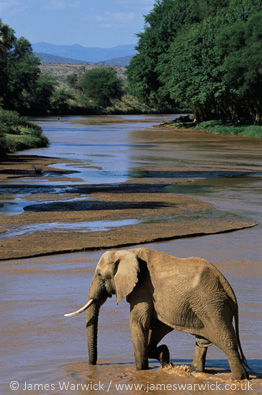

African elephants inhabit two general habitats, and as such are sometimes split into savannah elephants and forest elephants; savannah elephants occur in fragmented populations across eastern, southern and western Africa, while forest elephants are found in the western/central African tropical rainforests.

African elephants are active both during the day and at night, although they generally rest during the hottest hours of the day. They require a supply of fresh water and plentiful food, in the form of grass or browse – each elephant may consume 200-300 kg of food and 160 litres of water per day! The availability of food and water are the most important natural factors in determining the distribution of elephants. To find suitable conditions the animals may have to make annual migrations of several hundred kilometres. Often they migrate from a permanent water source at the start of the rainy season and return when the water holes begin to dry up at the beginning of the dry season. Consequently, home ranges have been measured as large as 3,120 km².

Elephants are highly social animals, and sometimes gather in groups of hundreds or even thousands of individuals (there is no evidence of territorial behaviour). Elephant society is essentially matriarchal, organised around a stable family unit of related females and their offspring. The clans are led by a large female, the matriarch, whose dominance is undisputed. The matriarch usually maintains her position until death, when she is succeeded by her eldest daughter. Males are normally driven out of the family group at puberty, which occurs at 8-20 years. After this time they tend to join small temporary all-male groups.

Elephants play an important role in the ecosystem they inhabit. They modify their habitat by converting areas of forest to grassland, and are important seed dispersers. They can provide water for other species by digging holes in dry riverbeds, and the wide paths they create as they wander through the forests act as firebreaks.

There were possibly as many as 27 million elephants in Africa in the early nineteenth century, but the 2002 African Elephant Database (AED) report the global population at fewer than 660,000 elephants. As a result of these population declines the African elephant is classified as Vulnerable to extinction on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Overexploitation of elephants for their ivory has been a major factor in the massive population declines over the past two hundred years. Hunting of elephants has soared at various times during the nineteenth and early twentieth century, in conjunction with increased demand from India and China following the decline of the Asian elephant, and later from Europe and the USA for the manufacture of billiard balls and piano keys. At the beginning of the twentieth century it is estimated that up to a thousand tonnes of ivory was being exported each year.

The 1970s saw another period of large-scale uncontrolled trade, and many populations were devastated, particularly in eastern and central Africa. In Kenya alone, numbers crashed from an estimated 167,000 in 1973 to just 19,000 in 1989. This exploitation also had profound effects on the age and social structure of elephant populations, with adult males and matriarchs being targeted by hunters for their larger tusks. In some areas there are now so few adult males that females may be unable to find a mate. The loss of a matriarch can have a devastating effect on a family unit, who depend on them for leadership.

Although hunting has decreased since the ivory ban came into effect in 1990, elephants are still hunted both legally and illegally for their tusks, and this exploitation remains a problem. This was a hot debate at the recent 15th Conference of the parties to CITES (The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species), with a victory for the elephants as the proposal from Tanzania and Zambia to downlist elephants to Appendix II failed to achieve the votes necessary to pass.

Habitat loss and fragmentation is now considered a serious threat to surviving elephant populations. Rapid growth of human populations, particularly in West Africa and the fertile east African highlands during the twentieth century, and the extension of agriculture into rangelands and forests have brought humans and elephants into direct conflict. The vast majority of elephants occur outside protected areas, and human-elephant conflicts occur when farming activities take place within this range.

To support the EDGE of Existence conservation programme for unique and threatened species, please donate here or become an EDGE Champion.