Piercing through the dark fog of pessimistic predictions for conservation’s future, rays of hope are appearing, in the guise of newly discovered species or subspecies. The last century has been a hotbed of new findings, including the mountain gorilla, the colossal squid, and EDGE species the saola (or Vu Quang ox, discovered in 1992).

Now every year, almost 20,000 previously unknown species are described by the world’s scientists and publicised worldwide in the media. Most recently there have been new caecilians, ‘tree lobsters’ that hadn’t been seen for 80 years, ‘Pac-Man’ and ‘cowboy’ frogs, and the world’s tiniest chameleon.

An increasing number of these are cryptic, which means they are ‘hidden’ subspecies of those that already exist, a recent example being the scalloped hammerhead shark.

Dr. Karl Shuker is a cryptozoologist who pursues species that are only rumoured to exist, which, with limited funding available, may be a risky avenue to take. The catch-22 is that once cryptids are known, research is taken out of Shuker’s domain by zoologists. Shuker believes so strongly that cryptozoology should be taken seriously that he is starting a new scientific journal devoted to evidence of the hidden animals, especially for cases where papers have not been accepted by the usual journals. However, the question remains whether it really is worth pouring conservation donations and grants into the possibly fruitless search for something that may or may not be out there.

A controversial issue that has arisen in the media recently is whether we should now keep these new species findings a secret from the media and public. The hype created by announcements about the discoveries may be fuelling the illegal pet industry.

In the case of Laotriton laoensis, a striking black and orange salamander found in 1999, local villagers were told by commercial collectors to gather as many as possible and sell them to buyers, and six years after its discovery it was close to extinction in the wild. Luckily in 2008, research by a local scientist in Laos helped make it illegal to trade wild-caught specimens.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is the leading organisation responsible for establishing the ‘endangered’ status of species on their Red List. However, some conservationists argue that labelling a species as endangered increases the value of them on the black market. Apathy from governments in third world countries perhaps highlights the need to target first world buyers of these illegally imported species instead.

Smuggling is clearly a problem for wild populations, but it might be more effective in the long-term to focus on stopping the decline in numbers due to habitat destruction, especially relevant with regard to amphibians. The answer might be to publish papers without specific locations of discovery, but this then prevents research being transparent to other scientists and could decrease co-operation between groups.

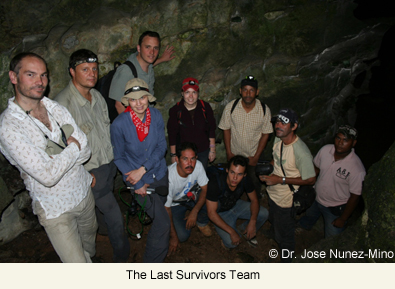

On a more optimistic level, there are now hundreds of conservation organisations around the world working towards securing animal biodiversity, and the movement shows no sign of slowing down. In the Dominican Republic in 2009, “The Last Survivors Project” was set up to help the Hispaniolan solenodon (a top 100 EDGE species) and hutia, the island’s only two remaining land mammals. The project is led by the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, funded by a three-year Darwin Initiative grant: the main focus is acquiring more information about the genetics and ecology of the two species, along with developing an island-wide monitoring programme and increasing local awareness.

The Zoological Society of London and EDGE are also actively involved as collaborators, providing support and publicity for the project from the UK. EDGE in itself currently has conservation projects for ten ‘focal’ mammals in various locations, details of which can be found here, as well as ten focal amphibians, representing a huge amount of biodiversity.

If you’d like to support us please visit our Champions page for some great fundraising ideas, or if you’re interested in applying to work with us as an EDGE Fellow we’re taking applications until the 31st of May 2012.