The circle of life is an accepted fact amongst biologists: some animals eat other animals to survive. Predator-prey relationships are key to keeping ecological webs stable, if either predator or prey die out then it changes the population dynamics of the ecosystem, the effects of which can filter right down to the human level, like what cereals we can eat or where we get our paper from.

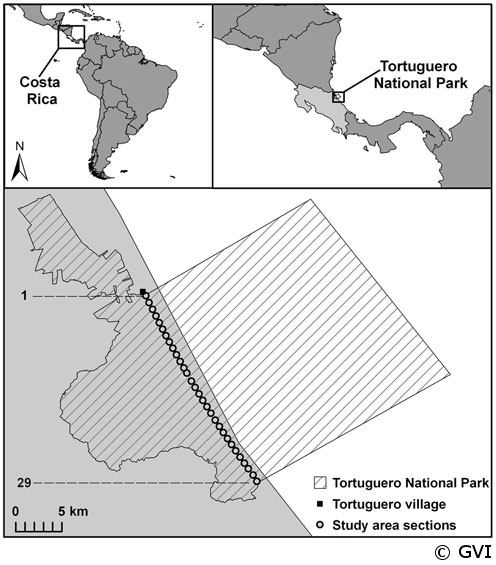

But what happens when human-caused environmental change forces a rare predator species to start eating endangered prey? This problem is likely to increase as humans encroach across more and more land, pushing animals to the edge of their habitat and into areas they wouldn’t usually go. A paper this week has published data showing that jaguars (Panthera onca), one of the most endangered big cats in the world, have switched their food source to endangered turtle species in Tortuguero National Park, Costa Rica.

The park is one of the largest green turtle (Chelonia mydas) rookeries, and it also contains a significant number of nesting populations of leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) and hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) turtles. There is currently no data on the jaguar population in the area, but they are considered to be highly threatened in Costa Rica, and the park (along with the adjoining Barra del Colorado Wildlife Refuge) is a priority Jaguar Conservation Unit.

Previously adult marine turtles were assumed to have no more than one or two irregular predators, so this was not considered an important factor. There was no significant predation before 1997, and in 2003 a study examining both species’ use of Tortuguero beach was stopped after just a year, providing no real data. Resuming the research on the same beach two years later, scientists were shocked to discover a record-breaking number of 676 jaguar-inflicted turtle deaths between 2005 and 2010.

Signs of jaguar attack seen were bite marks on the neck, with usually only the neck and flipper having been eaten, and drag marks in the sand around the turtle body. Most kills were in the central area of the beach as there is more human disturbance in the north and south. Diogo Verissimo, of the Durrell Institute of Ecology and Conservation and Global Vision International, blames deforestation and habitat degradation which is pushing the jaguars closer to the coast, but argues that conservationists can help reduce the turtle mortalities by actively making prey ‘more easily available’ in Tortuguero National Park.

The researchers are calling for more communication and acceptance of joint responsibility between different specialist conservation groups with problems like this that affect more than one species: only using ‘flagship’ animals for conservation management strategies may be detrimental in situations like this when two very high profile species clash, and limited conservation funding may always mean an agony of choice over which species ‘deserve’ investment.

Related links: