Mythical EDGE Species continued….

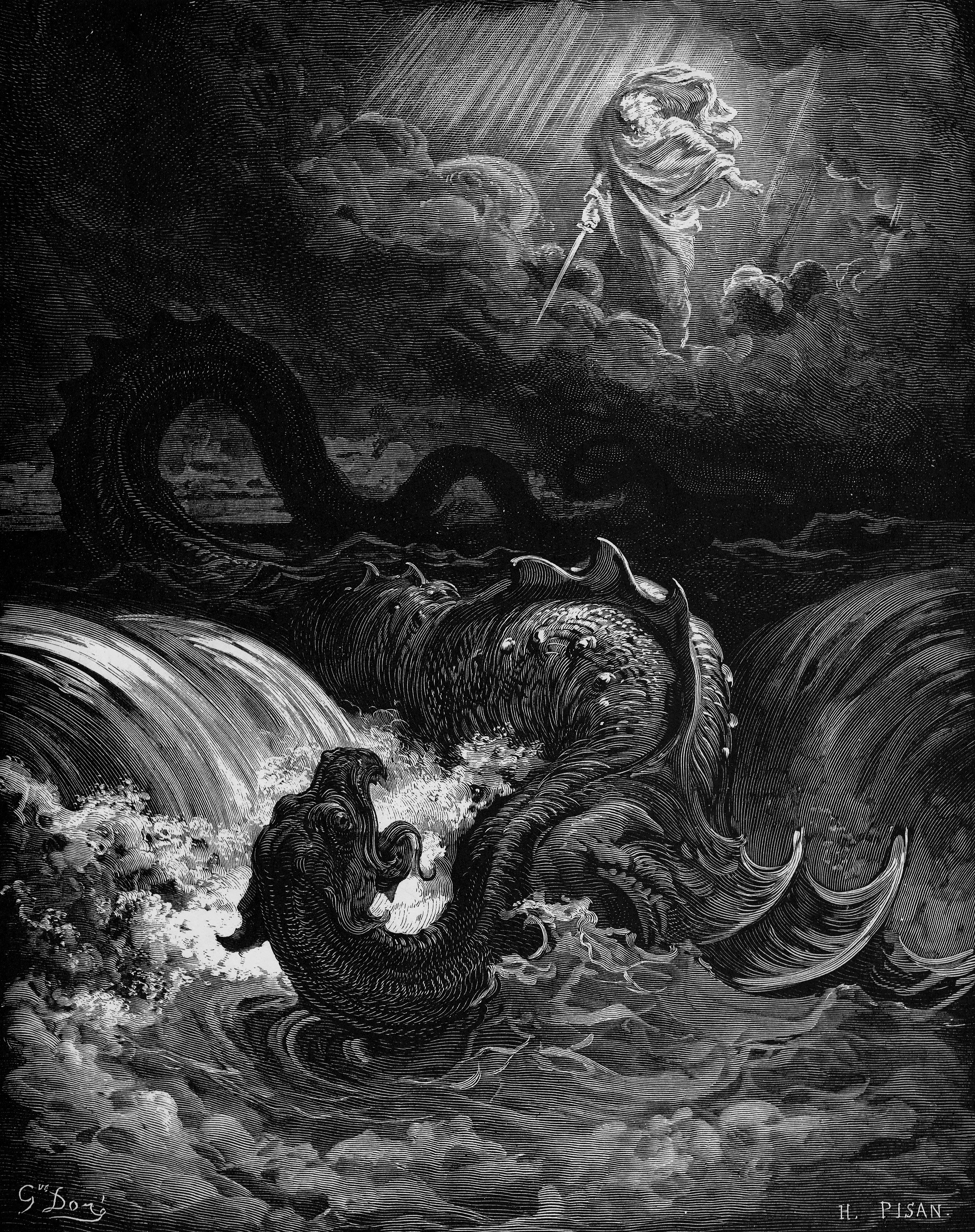

The Leviathan (Hebrew)

One of the earliest mentions of the Leviathan appears in the Tanakh, where it was described as a monstrous sea creature that breathed fire, had shield-like scales, and was impervious to arrows and swords. Some other sources referred to it as a sea serpent. As time went on, however, it became known as simply a giant sea monster. It was said that there were originally two leviathans, male and female, but that God slew the female and planned to serve her meat at a great feast, which would take place in a tent made of her skin. The leviathan was also said to be so huge it could swallow whales, and that it was three hundred miles long!

You could guess this one just by thinking really really big and marine… Yep, chances are the stories of the leviathan came from sightings of the blue whale. In contrast to many other species of whale, the blue whale’s body is long, slender and tapered, possibly leading to the impression that it was some sort of serpent.

It might not be three hundred miles long, but at 98 feet and 180 tonnes, the blue whale is the largest mammal ever known to have existed! Early sailors seeing this magnificent animal, many times longer than their boats, must have been awestruck. It’s easy to imagine how tales of their encounter could quickly have been spun into myth. In spite of the legendary whale-swallowing power of the Leviathan, however, the blue whale actually has a very narrow throat. Far from devouring whales, this leviathan would have difficulty swallowing a large orange!

Dragons (European)

Dragons are the mythological A-listers of many global cultures, from Asia to the US (helped along by Game of Thrones), and the of course UK is no exception. The patron saint of England, St. George, so the story goes, killed a dragon on Dragon Hill in Uffington, Berkshire, and it is said that no grass grows where the dragon’s blood trickled down the hill.

Legends of dragons in the UK have many of their roots in mainland Europe (St. George probably never even visited Britain). But there aren’t any reptiles on the EDGE list (yet!), so what bird, mammal or amphibian could have fuelled dragon folk law in Europe?

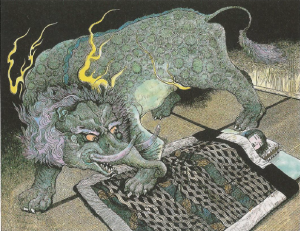

This bizarre-looking creature is an olm, a type of cave-dwelling salamander native to central and southeastern Europe. Because it lives deep within caves, it is rarely seen, and has developed a bizarre appearance: translucent, whitish skin with a pink tinge due to blood capillaries running near the surface and three pink external gills on each side of the head. They also have poorly developed eyes, which are even skin-covered in one subspecies. It’s perhaps no wonder that when people first saw it they thought it was something intriguing and maybe even supernatural.

The first written mention of the olm is in 1689 in Janez Vajkard Valvasor’s publication “The Glory of the Duchy of Carniola” where the species is desrcribed as a baby dragon in reference to an old folk story. He came across them while studying in Slovenia during a period of heavy rain. Water bubbled up from underground caverns, apparently bringing with it several olms, washed out from subterranean caverns by the rains.

So while the olm may not be the origin of dragon mythology (a lofty claim to fame for any animal), it certainly makes up part of the dragon’s tale which is clearly still captivating to this day.

Baku (Japan)

The story goes that, after the gods had created all of the other animals, they decided to make one last one to use up all the parts that were leftover. An elephant’s trunk, an ox’s tail, a tiger’s feet, a bear’s body… all together they made the bizarre chimera known as the baku. The legend originated in China, but later became known in Japan as the eater of dreams. If a child in Japan wakes from a nightmare, all they have to say is, “I give this dream to the baku” or, in some areas, repeat “Baku-san, eat my dream” three times, and the baku will come and eat the nightmare so that it can never trouble the child again. But that child should beware; a hungry baku may also eat their hopes and desires as well, leaving the child to live an empty life.

The Asian tapir bears a very striking resemblance to the baku above, and indeed, the term “baku” is used to refer to both the mythical baku and the tapir. Notice a certain similarity?

The Asian (or Malayan) Tapir is not actually found in Japan at all. It’s current range is highly fragmented, but in the past it ranged across Southeast Asia. It’s possible that Chinese travellers originally encountered the tapir, and as the story spread to Japan, somewhere along the way the tapir became known as the baku. Throughout Japanese history, talismans and even pillows of the baku have been used to ward off evil spirits and dreams, and as time went on the mythical beast and the tapir became all the more interchangeable.

In modern Japan, the baku has shifted to look more like the tapir rather than the chimera of the past. It’s common to see tapir-shaped pillows and charms for sale as sleep aids in Japan, and the Asian tapir is still known as a dream-eater today.

And the final “mythical” EDGE species is…

The Unicorn

It’s a centuries long case of mistaken identity. The rhinoceros, the narwhal and the oryx are all creatures allegedly responsible for the persistent myth of the unicorn. But we have a new animal to add to the list: the saola.

The earliest description in Western literature of a single-horned “wild ass” was by the Greek doctor Ctesias in around 4th century B.C., who claimed that the animal was the size of a horse, with a white body, purple head, and blue eyes, with a long horn coloured red at the tip, black in the middle and white at the base. It was said to be very so fast that “no creature, neither the horse or any other, could overtake it” and difficult to capture. Ctesias probably never saw the animal for himself, instead he came up with this image after hearing people’s accounts, likely fusing details of multiple creatures including the Indian rhino.

At the time the description probably sounded no more bizzare to Ctesias than the image of an elephant or a giraffe.

In the Far East, similar mythological creatures were also being created. The Japanese ‘kirin’ is portrayed as a fierce animal able to root out criminals and punish them by piercing them through the heart with its horn. The Chinese ‘qilin’ was a peaceful animal who’s presence was seen as a good omen.

The Western and Eastern versions of the myth sometimes crosses paths too:

“There are wild elephants and plenty of unicorns, which are scarcely smaller than elephants. They have the hair of a buffalo and feet like an elephant’s. They have a single large, black horn in the middle of the forehead… They have a head like a wild boar’s and always carry it stooped towards the ground. They spend their time by preference wallowing in mud and slime. They are very ugly brutes to look at. They are not at all such as we describe them when we relate that they let themselves be captured by virgins.”

–Italian explorer Marco Polo, c. AD 1300, most likely describing a Sumatran rhinoceros

This beautiful animal is an EDGE Mammal called a saola, and while it may have two horns, it has much more in common with the mythical unicorn than you might think. Saola’s are restricted to remaining forest in the Annamite Mountains between Vietnam and Lao PD, and are one of the few species of antelope adapted to life in the forest. They are also extremely elusive and rare, earning it the nickname “the Asian unicorn”. In fact only four saola have ever been photographed in the wild.

But there’s more to it than that.

The Hmong people of Laos call it saht-supahp, or “the polite animal”, because the saola moves silently through the forest, leaving no trace of its passage. When it eats, it does not yank or tear leaves from branches, preferring to gently chew the leaves off their twigs, making no noise and breaking no branches. Finally, despite being stressed by captivity, those saola that have been caught and held are reported to be incredibly quiet and docile. Keepers and scientists were able to hand-feed the animals, pet them, and even pick ticks out of their ears. Considering the rarity of the saola, it must have felt to those people like being able to touch an actual unicorn.

So, there you have it. Five mythical creatures that exist today in some form as EDGE species. See Part 1 if you haven’t already for five more mythical EDGE species! While they may not sniff out gold or spit lightning, these weird and wonderful animals have been igniting human imagination for thousands of years. Please help us to keep these animals from becoming true myths by donating or fundraising for EDGE!