I beg your pardon, dear reader, for beginning with some personal context before delving into the subject of my project. My name is Gabriel Carvalho de Ávila, and I am an EDGE Fellow, part of the 2024 EDGE Fellowship. But my story doesn’t begin here. Years ago, when I graduated as a biologist, I had a shallow understanding of what nature conservation truly meant. To me, it was simply some humans helping animals and plants protect themselves from other humans, a disconnected, stratified, and often contradictory or even conflicted perspective. Today, I realise I was only seeing the most obvious pieces on the table, missing the full picture that only emerges when all the parts come together and are observed from a distance. My shift in perspective was a long and natural process, shaped by the practical challenges of environmental management and the search for feasible ways to tackle them. A big part of this, though, came from the demands of my job in a protected area, having to engage with very different groups: researchers, tourists, big business owners, politicians, and, most importantly, local communities. Locals often have a worldview that I initially overlooked in my scientific analysis. Yet, time and again, it was their unassuming insights that led me, if not to a solution, then at least to a fairer and more balanced approach to complex issues in environmental conservation.

I beg your pardon, dear reader, for beginning with some personal context before delving into the subject of my project. My name is Gabriel Carvalho de Ávila, and I am an EDGE Fellow, part of the 2024 EDGE Fellowship. But my story doesn’t begin here. Years ago, when I graduated as a biologist, I had a shallow understanding of what nature conservation truly meant. To me, it was simply some humans helping animals and plants protect themselves from other humans, a disconnected, stratified, and often contradictory or even conflicted perspective. Today, I realise I was only seeing the most obvious pieces on the table, missing the full picture that only emerges when all the parts come together and are observed from a distance. My shift in perspective was a long and natural process, shaped by the practical challenges of environmental management and the search for feasible ways to tackle them. A big part of this, though, came from the demands of my job in a protected area, having to engage with very different groups: researchers, tourists, big business owners, politicians, and, most importantly, local communities. Locals often have a worldview that I initially overlooked in my scientific analysis. Yet, time and again, it was their unassuming insights that led me, if not to a solution, then at least to a fairer and more balanced approach to complex issues in environmental conservation.

Working in the management of a public protected area gave me the chance to see conservation from many different angles. In a country like Brazil, biodiversity conservation and economic development are both legitimate demands, yet they often end up at odds with each other. I realised that seeking conciliatory paths in the landscape and human hearts could be a promising strategy for conservation. But my greatest lesson was this: Nature itself is the ultimate teacher of conservation, and through its own means, it can achieve results beyond our wildest imagination.

The Red-billed Curassow (Crax blumenbachii) the focus of my EDGE project, is not merely an endangered bird species; it is a symbol of the serious and unwitting consequences for nature of human actions. This bird originally inhabited a stretch of Brazil’s Atlantic Rain Forest, between the states of Bahia and Rio de Janeiro. Its habitat was among the first targets of the environmental changes brought by colonisers, replacing landscapes once managed solely by Indigenous peoples.

Like so many other species, the curassow found itself, within just a few years, without a home, forced to face new and growing challenges to survive. The bird resembles (and is evolutionarily close to) a chicken. Due to its large size and terrestrial habits, it became an easy target for hunting, whether by humans or their domestic animals. Additionally, the curassow feeds on fruits, insects, worms, and small animals, requiring tall trees for nighttime shelter and nesting. These “requirements” mean its survival depends on mature, well-preserved, and extensive forests. As an inhabitant of Brazil’s most degraded biome, finding a suitable home became nearly impossible for this species.

This dire situation could only have one outcome: today, the curassow has become extinct in nearly all the forests it once called home.

This bird holds great significance for humans. Beyond being a food source for Indigenous peoples and later settlers, it is a beautiful, charismatic animal that fosters forest diversity, dispersing seeds and turning over the soil’s organic layer. The curassow is, by all means, an amazing forest gardener! So, when we lose curassows, we lose something vital, not just for ourselves, but for every living thing in the forest.

Fortunately, some visionary humans realised that curassows stood little chance in rapidly degrading natural habitats but could adapt to human-assisted breeding. At first, this might seem like a cruel fate for a bird, condemned to live behind bars. Yet, the rescue of a few wild curassows by conservationists decades ago allowed for the development of captive breeding techniques, which in turn made their reintroduction into the wild possible.

CRAX, a Brazilian conservation breeding centre, has supported the reintroduction of endangered birds. Their efforts ensured a population of curassows that could be used in reintroduction projects. One standout initiative is their partnership with CENIBRA S.A., a company that has released curassows in its private reserve in eastern Minas Gerais since 1991.

The success of this project encouraged its leaders to seek a location offering greater long-term survival prospects despite ongoing threats. The Rio Doce State Park, the largest Atlantic Forest reserve in Minas Gerais, emerged as the ideal “Noah’s Ark” for the species.

Reintroducing a species is a complex and uncertain process, often far more challenging than protecting one that is still present in the wild. Even after the first reintroductions, we still faced critical doubts: Would these captive-born birds adapt, survive, and thrive on their own? Could they learn to feed, shelter, and reproduce in the wild? These uncertainties made us question whether success was truly within reach.

At this point in our story, an unexpected twist unfolded. As we prepared to release 30 curassows near Rio Doce Park, their calls attracted unexpected visitors: a wild pair, likely descendants of curassows released in the 1990s. A miracle! Curassows were already settling in again in the area. These birds had dispersed across vast distances, navigating cities, highways, eucalyptus plantations, farms, dogs, and humans, yet they managed to return on their own.

This revelation was a much-needed boost for our project. It proved that earlier reintroductions had succeeded beyond expectations, not only sustaining populations but enabling them to colonise new areas. Moreover, captive-born birds now had wild mentors, increasing their survival odds. Nature had always held the reins, and the curassow was more resilient than we imagined.

After releasing about 40 birds, we documented a lot of good news: first, we found a wild pair (unbanded) with a chick near the enclosure area. Second, the released birds (banded) were forming mixed flocks with wild ones. And, after all, Curassows were entering the park, a historic return after 50 years of absence was registered.

The species return to the park is particularly significant. For engineering reasons, our acclimatisation aviary had been built just outside the park, close by, but on the other bank of the Doce river. We were hoping the Curassows would cross the river and settle in the park, but that was a bit of a gamble. We bet on nature, and it paid off. The Curassow was back in the Rio Doce State Park, after nearly half a century!

Today, some released birds have been spotted in remote areas of the park, surviving for over two years. While we have yet to confirm banded birds breeding, the signs are promising.

But nature had more lessons to teach. Some released birds ventured into nearby urban areas, forcing us to confront a new reality: we couldn’t save the curassow without including the local people. Unlike projects that hide endangered species from locals to protect them, the curassow demanded interaction. This led to a profound shift in our approach:

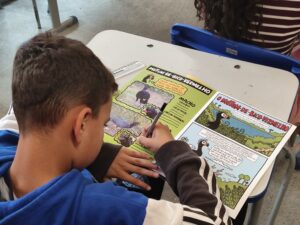

The community had to become part of the solution. This shift of the project approach was challenging but brought to us new promising perspectives: Locals could aid in monitoring process and protection. Taking the curassow to the community, the bird could become a symbol of unity, not division.

Dear reader, let’s be pragmatic: much work remains to secure the curassow’s long-term recovery in Rio Doce State Park. Efforts that began in the 1990s may still need decades more to fully succeed. Yet, the lessons from nature, and from this resilient bird, are too precious not to be celebrated.

If this story has moved you, I leave you with a question:

Is there any ill on this planet that nature cannot heal?