It‘s the world’s rarest antelope, a unique, Critically Endangered species which is has received little media or conservation attention. So…who’s heard of the hirola?

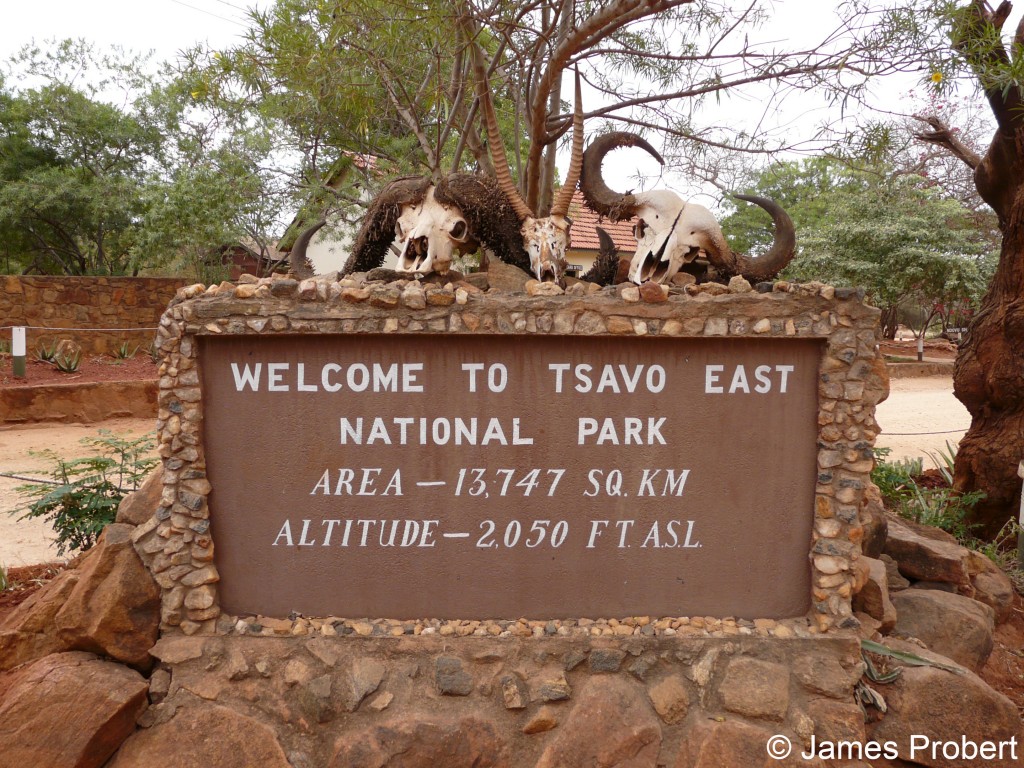

Hirola are medium sized antelope native to an area of around 40,000km2 on the Kenyan-Somali border. In the 1970’s and 80’s the native population declined by more than 90%, prompting conservationists to establish a safeguard population in Tsavo East National Park. Despite initial breeding success the Tsavo population stagnated and the last population survey in 2000 found just 77 individuals.

This is where I come in.

In early 2011 I was a master’s student studying Conservation Science at Imperial College London. It had been over a decade since the last survey of the hirola population in Tsavo and a drought in the region had severely impacted several other species. There was uncertainty and concern about the status of the hirola in Tsavo and I was about to depart for Kenya to survey the population as part of my master’s dissertation.

Accompanying me was Ben Evans, a fellow Conservation Science student at Imperial. Ben is also Kenyan and his knowledge of Kenya, fluency in Swahili and 4WD would prove vital to our project’s success. Ben and I collaborated to survey the hirola population but we also wanted to know why the population wasn’t increasing. Ben focused on predation as a limiting factor and I focused on the suitability of the vegetation in Tsavo.

Our task was daunting to say the least. Tsavo covers over 22,000 km2, 4% of Kenya’s total land area, and we were searching for 77 beige antelope in a vast landscape that, at that time of year, was predominantly beige.

We had permission from Satao, one of the tourist lodges, to camp in the bush behind their staff quarters. We ate dinner in the staff canteen, which meant a diet of ugali (a heavy dough like paste that sits in your stomach like a cannonball) and beans, washing was courtesy of a bucket and when we needed to shave or cut our hair we did so in the wing mirror of our 4WD. Needless to say the results left something to be desired.

Camping in the bush meant the local wildlife were part of our daily lives. Franklin (African partridge) squabbled over the crumbs from our breakfast, we regularly had to remove scorpions from our beds, fought a daily battle against a troupe of baboons intent upon raiding our food stores, elephants wandered through our camp at night and on one occasion a large male lion killed an impala and spent two days leisurely consuming it barely 100m from our tents.

Whilst I appreciate that, for many people, what I describe does not sound like a relaxing holiday, I assure you that for a biologist it was absolute heaven!

Ben and I spent 12 weeks in Tsavo, conducting surveys on and off road for between 6 and 8 hours every day. We also conducted an aerial survey with the help of the Kenya Wildlife Service, spent hours searching for predator scat for Ben’s projects and then more hours surveying vegetation for mine.

As is the tendency of biologists in the field, we acquired various items of interest during the course of our fieldwork. An assortment of skulls, hooves, horns, tusks, teeth, scraps of hide and even broken elephant tusks began to accumulate into a slightly macabre shrine in one corner of our camp.

In addition to the vital data we needed for our dissertations our fieldwork gave us an incredible opportunity to observe Tsavo’s wildlife. We saw plenty of lion, cheetah, hippo and zebra, being charged by elephants became a mundane nuisance, but we were most delighted to see honey badgers, aardwolves, bat eared foxes and a melanistic serval. Most evenings we would drive to a secluded spot and have sundowners (that’s beer whilst you watch the sunset) before heading back to camp for an early night.

The fruits of our labour were our dissertations. A total of 195 pages of crisp white paper were a sharp contrast to the red dust and sand of Tsavo. Our results showed that the drought hadn’t had as big an impact as we had feared and the hirola population in Tsavo remained stable at 67 individuals. They also showed that there is relatively little high quality hirola habitat in Tsavo, perhaps explaining why hirola numbers have remained static.

The future is still uncertain for the hirola. The majority of conservation efforts are directed at the natural population but the hirola in Tsavo remain a valuable insurance policy. The extinction of the hirola would be the first loss of a mammalian genus in Africa since the evolution of modern man. With a global population of less than 400 individuals we cannot allow this unique species to slip through our fingers.

Our research demonstrated that, whilst the Tsavo hirola population remains small, it has also been stable for decades. As long as it remains stable the hirola in Tsavo are fulfilling their role as a safeguard for the species and the majority of conservation attention will be focused on the natural population. A sanctuary surrounded by predator proof fencing has recently been built in Ishaqbini and the hirola there are breeding well. In Tsavo the focus will be on monitoring the hirola to make sure the population continues to survive.