Marvel Comics brought you X-Men in 1963; spandex-uniformed human genetic anomalies or “mutants” with super powers hinted at by their names, e.g. Iceman, Beast, Storm and, notably, the villainous Toad. As an enthusiastic homage, the EDGE of Existence programme now brings you X-Frogs because we noticed that there are few things that the X-Men get up to that can’t be matched by a crowd of diverse and remarkable EDGE Amphibians.

Hence, our multi-part blog on X-Frogs will bring you some of the strangest behaviours of the amphibians through an attempt to find parallels with the comic book X-Men heroes.

You think it can’t be done….?

PART ONE – WOLVERINE…

X-Man Wolverine possesses animal-keen senses, enhanced physical capabilities, and a healing ability that allows him to recover from virtually any wound. This healing ability enabled the “Supersoldier Program Weapon X” to bond the near-indestructible metal alloy “adamantium” to his skeletal system. As a result, retractable metal blades surge from his fists during combat…the ultimate secret weapon.

Well, amphibians are now known to boast a secret weapon of their own to rival Wolverine’s hidden extras. As reported in the scientific journal Biology Letters by David C. Blackburn, James Hanken and Farish A. Jenkins Jr. of the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University in the article “Concealed weapons: erectile claws in African frogs” it is now official – some frogs can kick butt Wolverine-style!

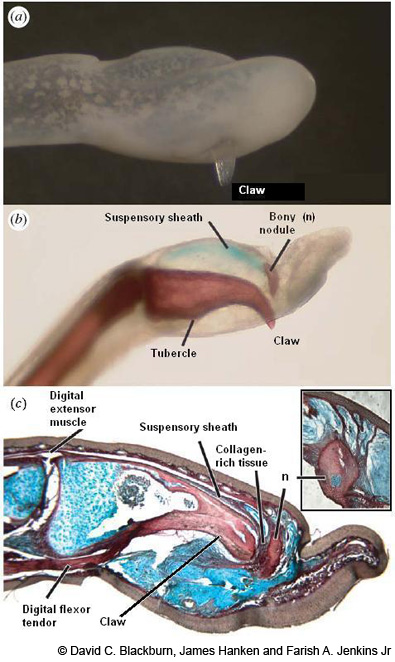

Claws of the hairy frog (Trichobatrachus robustus)

Vertebrate claws perform a variety of important purposes and are typically composed of a keratinous sheath (i.e. the same material that constitutes mammalian hair and fingernails) overlying the terminal bony portion of a digit. Claws are variously employed in locomotion, prey capture, feeding, defense and a range of other behaviours. Keratinous claws are rare in living amphibians and, where present, they are sufficiently different from mammalian claws to be considered independently derived by convergent evolution – i.e. the structure of the claw emerged more than once in different part of the evolutionary tree of life.

The claws of Tyrannosaurus rex are among the largest recorded

Blackburn, Hanken and Jenkins Jr.’s recent study of some African frogs has revealed another type of claw that is unique in design among living vertebrates and lacks a keratinous covering. Certain African frogs (Family: Arthroleptidae) struggle and kick violently when picked up, raking their erectile, bony claws to inflict cuts in their antagonist’s skin.

Initially observed 100 years ago by researchers, these claws were originally deemed an artifact of the preservation process. Recent research at Harvard University represents the first detailed anatomical study and interpretation of these specialised structures. In fact, David Blackburn was especially keen to solve the mystery of these claws after undergoing frequent maulings by these frogs during his research trips to Cameroon. He has commented: “The frogs will start kicking and drag these claws against your skin. I’ve gotten bloody scratches from them many a time.”

David C. Blackburn

X-Frogs are EDGE-Frogs…

In two genera studied, Astylosternus (the “night frogs” – 11 member species) and Trichobatrachus (the “hairy frogs” – with just one member species), the terminal portion of the 2nd to 5th toes is distinctly claw-shaped with a markedly downturned, pointed tip. The genera are both present in the “screeching frogs” group of a frog family called the Arthroleptidae, which represents a portion of the amphibian tree of life rich in EDGE Amphibians and evolutionarily distinct species in general.

The highest placed EDGE night frog is the Nganha night frog, ranked 73, and there are seven other EDGE night frogs (up to lowest rank of 578).

Arthroleptidae frog: Astylosternus rheophilus

The hairy frog (Trichobatrachus robustus) is not currently endangered, but lies within the top 3.5% of the most evolutionarily distinct amphibian species. Incidentally, the hairy frog is extremely peculiar for another reason – during the breeding season the males grow hair-like skin projections along the sides of their body, lending them a shaggy appearance. This is thought to enhance oxygen uptake from the water during this particularly energy-expensive time. The males sit guarding the eggs they have fertilised for long periods of time, and these “hairs” probably assist in respiration through the skin since they cannot use their lungs in the water.

Hairy frog at the Natural History Museum, London

But I digress…

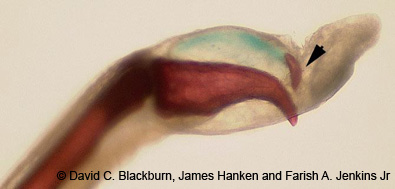

Structure of the claw…

The special Wolverine-frog claws are located internally on digits of the hind limbs and become functional by cutting through the skin. In the resting state, each claw is found underneath the skin and is attached to a bony nodule via collagen-rich connective tissue. When erected, the claws break free from their nodules and pierce the skin of tips of the frog’s toes. Each nodule remains fixed in place because they are suspended by a sheath attached to the terminal portion of the each digit (also referred to as the “terminal phalanx”) and supported by collagenous connections to the skin. When forced through the skin, these claws superficially resemble the shape of claws in other tetrapods (four-limbed vertebrates), but these are the only vertebrate claws known to pierce their way through skin to become functional.

Anatomy of the claws of Astylosternus and Trichobatrachus

Furthermore, it seems that “Wolverine frogs” can be male or female, young or old – no evidence has been found of sexual dimorphism in the presence, number or morphology of the claws and these structures are employed similarly by juveniles and adult male and female Astylosternus (D.C. Blackburn 2006, personal observation).

What are the claws for?…

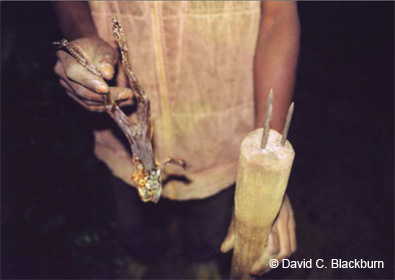

G. Kingsley Noble was the first to attribute a functional significance to these claws in 1931 in his book “The biology of the Amphibia”, speculating that they may provide a “surer grip before leaping” (p. 517). Gerald Durrell later reported in “The Bafut beagles” (1954) when handling a live hairy frog that these claws are used for defense as they can inflict “deep bleeding wounds [to] the person holding it”. This claim is verified by Cameroonians who hunt hairy frogs for food using long heavy spears (see picture below) or machetes such that they can kill the frogs without handling them and being harmed. Ironically, the Cameroonians have produced Wolverine-type weaponry of their own to subdue the hairy frog – the three blades of their purpose-built spears mimicking this X-Man’s three-bladed fist!

Cameroonian hunter holding a fire-roasted subadult male Trichobatrachus (left) and a spear (right) used specifically to hunt this frog species (near Ntale, Southwest Province, Republic of Cameroon; September, 2004). The frog pictured was captured during a nighttime hunt and killed by this local hunter via a machete wound to the head.

Does claw projection hurt these Wolverine-frogs?…

Quoting from the film X-Men (2000) – Rogue and Wolverine are having a conversation about his retractable blades…

Rogue: When they come out… does it hurt?

Wolverine: Every time.

As is the case for Wolverine, these X-Frogs probably do feel a degree of discomfort when unleashing their secret weapons. The emergence of the claw causes a traumatic wound as the skin is torn. Because the bony nodule is firmly anchored via collagenous tissue, it remains embedded within the fleshy digit tip when the claw is exposed. The claws of living specimens of these frogs appear to move in and out of the skin of the digit tip, although it is unclear whether retraction is active, passive or a combination of both. David Blackburn has only studied dead specimens and is therefore not entirely sure what happens when the claw retracts – or even how it retracts. Since it does not appear to have a muscle to pull it back inside, the reserach team think it may passively slide back into the toe pad when its attaching muscle relaxes.

More claw?….

The resting claw is supported by an attachment to the nodule, which is anchored by a suspensory sheath and collagenous strands to the skin layer. These connections may inhibit the erection of the claw during normal non-defensive behaviours. A digital flexor muscle inserts via a robust tendon on a point of attachment on the lower surface of the claw. Blackburn, Hanken and Jenkins Jr. propose that the activation of this muscle flexes the claw that then breaks away from the nodule and pierces the skin of the toe tips, thus exposing the barb-like tip that is reinforced by cortical thickening.

Close up of the exposed claw projecting through the skin of the tip of the toe

After becoming erect, the claw may passively return to its resting position. As remarkable regenerative capacity is documented in many amphibians (e.g. most newts and salamanders can regrow whole limbs), the subsequent healing of the broken skin and underlying connective tissue surrounding the claw would be well within the common capabilities of the average amphibian, but this has yet to be documented. Similarly, the possible regeneration of the connection between the claw and the bony nodule, and thus the return to the resting state of this functional relationship, remains to be evaluated. David Blackburn has commented: “Being amphibians, it would not be surprising if some parts of the wound heal and the tissue is regenerated“. Hence, these frogs could well retract their claws, swiftly heal and live to fight another day, just like….Wolverine!

As mentioned above, no other vertebrate claw has been reported that lacks a keratinous sheath, is composed solely of naked bone, and must break free from another skeletal structure to pierce its way to functionality through the skin. However, the “Wolverine frogs” are not alone in their propensity for producing anatomical weaponry to give them the upper-hand in all manner of amphibious combat…males of many distantly related frog species have bony spines in their hands and/or feet that can project through the skin for use in male–male fighting.

X-Salamanders…

Chinhai Spiny Newt (Echinotriton chinhaiensis) –with warning colouration on the underside of the hands

Not to be outdone, the salamanders have gone one step further in their bid to develop the world’s most bizarre secret weapon. The “spiny newts” of the genus Echinotriton (such as the Chinhai spiny newt – EDGE rank 68) are so-named because of their remarkable defense mechanism against predators. They have sharp, elongated ribs whose tips project through the skin when these animals are grasped. The rib tips of the spiny newts pass though enlarged glands on the sides of the body, and painful skin secretions are injected into the mouths of would-be predators. They also exhibit a rigid antipredator posture, during which the body is flattened and curled up and the hands and tail are raised, revealing red “warning” markings.

Chinhai Spiny Newt (Echinotriton chinhaiensis) – viewed from the top

The amphibians have therefore satisfactorily evolved counterparts of Wolverine’s blades of terror. If it existed, we’re pretty sure that they would be accepted into Professor Xavier’s School for Gifted Youngsters, but for now they remained honoured members of the EDGE Amphibians.

Wolverine frogs….whatever next?

Part 2 – Iceman….coming soon!

Information reported with permission from the lead author:

Blackburn, D.C., Hanken, J. and Jenkins Jr., F.A. 2008. Concealed weapons:erectile claws in African frogs. Biology Letters.

See also:

Make Way for Superfrog. Lauren Cahoon – ScienceNOW Daily News,

28 May 2008

‘Horror frog’ breaks own bones to produce claws. Catherine Brahic – NewScientist.com news service, 28 May 2008

Frogs Pack Concealed Claws. Charles Q. Choi – LiveScience, 27 May 2008.