Jose de la Cruz Mora is one of our Segré EDGE Fellows who is working in Cuba to protect his EDGE species – the Cuban greater funnel-eared bat (Natalus primus). In this blog he writes an introduction to Cuban bats, highlighting their importance for the local environment and the threats they face.

Cuba has 26 living species of bat, the richest collection in the West Indies, representing more than 45% of all species in the region. Being an island, Cuba’s wildlife arose thanks to multiple colonisation and extinction events, leading to its current high abundance of small vertebrates and endemic species. Jose explains that Cuba’s wildlife is 70% bat species which arrived and survived on the island thanks to their ecological flexibility and fast adaptation.

Bats and Ecosystems

Bats hold the key…

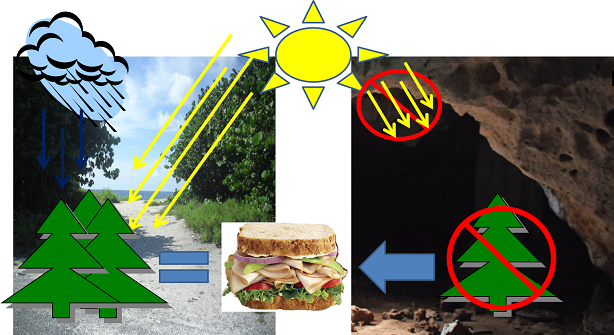

Bats are a key part of the Cuban ecosystem, helping to maintain its structure and function through their roles as pollinators – second only to bees on the island. Fruit eating bats, for example, play a role in building forests thanks to their feeding strategies:

“One of the most common strategies of fruits eating bats is to transport fruits, as heavy as 1/4 of their body mass, far from their original tree to a safe branch to eat it. This behaviour distributes millions of seeds every night, helping to create new forests and preserve the structure of existing trees.”

Bats also play an important role in maintaining human health on the island. Since many eat insects, bats help keep numbers manageable:

“More than 2/3 of all bat species diet is constituted by insects. Bats are the highest and more efficient plague control machinery in Cuba and the world, consuming 1/4 of their body mass every night in mosquitos and other insects that affect human health.”

Why so many?

Bats inhabit all of the different terrestrial ecosystems found in Cuba. This is thanks to the island’s large area, its abundance of suitable bat habitats (like caves) and its close proximity to other landmasses (North and Central America). Jose outlines how so many bats can live together in Cuba:

“It’s common to find high densities of more than ten bat species sharing the same patch of forest. In some areas such as La Barca, sixteen bat species can be found sharing this dry forest close to the sea. This type of habitat use is possible as each bat species has evolved to use different resources in the forest and at different times, meaning the bats don’t compete for resources. This nifty ecological adaptation is otherwise known as species segregation.”

Bats and Caves

Although bats are also found in forests and swamps, one location they are both famous for and indispensable in is caves. Bats help preserve the wildlife and the dynamics of the caves they inhabit.

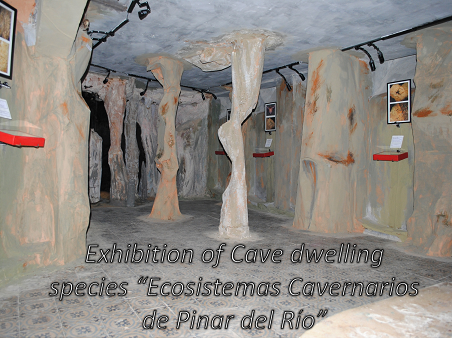

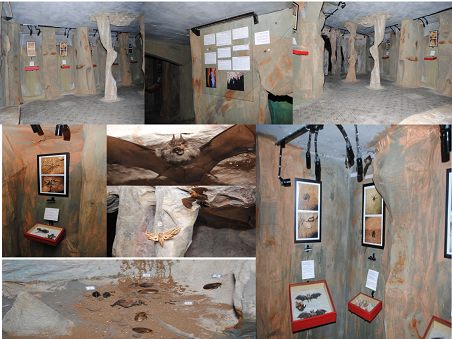

Cuba has no shortage of caves, with regions like Pinar del Río being particularly abundant. Most terrestrial environments rely on trees to produce fruit which act as an energy source for the entire food chain. However, caves don’t have trees so bats fill in the gap. Returning to their roosts after foraging, the bats carry resources back with them. Inevitably some of the food falls to the cave floor where it is eaten by small cave micro-fauna. These organisms are then eaten by larger insects which are in turn eaten by even larger vertebrates at the top of the food chain. In this way, bats keep the whole ecological system running. Jose adds however that the bats don’t remain unchecked:

“In Cuban caverns, the top of the food chain is occupied by the Cuban owls and the Cuban boa (Epicrates angulifer) which prey on the bats, keeping their numbers under control.”

Cuban Bats

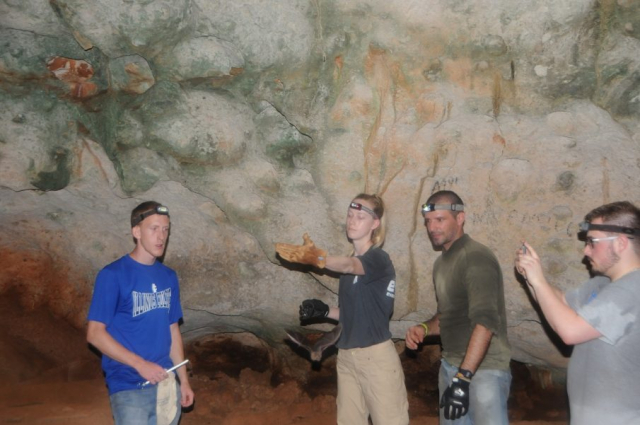

Despite being well studied, many people still don’t like bats. Jose believes that this fear has arisen thanks to how bat habitats look – dark and ominous. On top of that Jose says, many people describe bats as “rats with wings” and the widespread association of the animal with vampires in cinema hasn’t helped their image. He also adds that the fear of contracting infections or diseases from bats has meant that complete colonies are often exterminated.

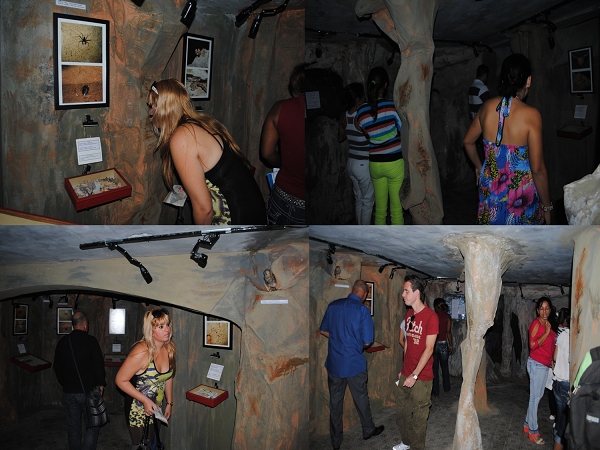

Through his research, Jose hopes to increase people’s appreciation for bats. He believes firmly in the importance of specialists:

“Once people see bats in the hands of a specialist, the ideas of fear and repulsion go away. This is never more evident than in children, who show a huge enthusiasm and interest in these old-new mammals.”

He also believes that to bolster his current conservation efforts new generations of researchers, scientists and social communicators must be trained. Led by Museum of Natural History “Tranquilino Sandalio de Noda” of Pinar del Río province, Jose hopes that a training programme will help change the misconceptions people have about bats. The programme has already involved actors from the Pinar del Río University, local primary schools and two National Parks in Western Cuba.

Bat Research Methods

Researching bats hasn’t always been easy: “The methods used involve invasive capture equipment such as mist nets which stress the captive bats and could affect then physically” but Jose is thankful for new technology:

“The advance of new technologies allows the study of bat communities using not invasive methods, such as the night vision photography and video or the ultrasound bat detectors. The use of photo and video cameras give the possibility to get new information about the life dynamic of bat species and their ecological interactions. Other important benefits are that this information has a strong visual component, highly important to support the educative mission of the museum and the national parks.”

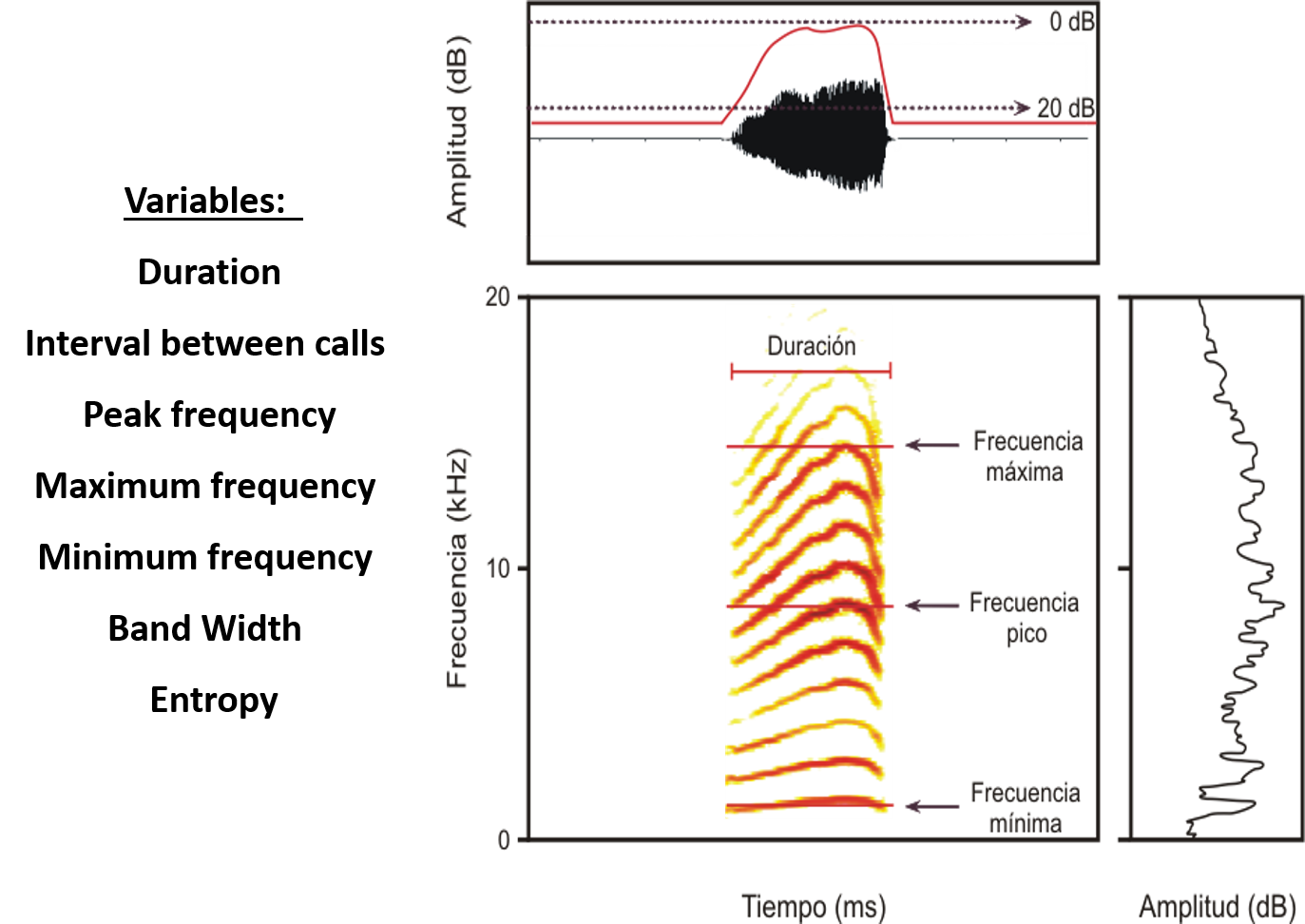

Jose explains that ultrasound bat detectors are key pieces of equipment that help study bat communities. Non-invasive in nature, the detectors can be regularly used without disturbing the bats – allowing them to exhibit natural behaviours and community dynamics. Scientists can use audio monitoring to accurately map bat community composition as each bat species has a unique call, its own audio stamp:

“These structural characteristics of the calls are so specific that they can be used for the identification of species of bats using their echolocation calls. The ecological studies based on sound recordings are very efficient at characterizing the structure and composition of bats communities.”

Bat Threats

When talking about the threats facing bats, Jose is very realistic in his view:

“The greatest threats to the survival of Cuban bats are the destruction of forests and the modification of caves, the latter being critical habitats for the mostly cave-dwelling Cuban bat fauna. We argue that its conservation should be the result of a cooperative effort promoting research and habitat management.

Four out of the 26 extant bats of Cuba should be considered endangered, four vulnerable to extinction, twelve potentially threatened, and six in a stable situation. Most of the species of bats endemic to Cuba are under some form of threat.”

Read more about Jose’s EDGE species and project here.

Jose de la Cruz Mora is a biologist, specializing in Cuba’s bat ecology and conservation. A graduate of Havana University, he is a full time researcher at the Museum of Natural History of Pinar del Rio Province. He participated in various research projects at national and international levels. He has also contributed to several conferences in Cuba and outside the country and was awarded five Academy Primes granted by the Academy Science of Cuba. He is a member of the Program for The Conservation of Bats in Latin America, the Cuban Zoological Society and the EDGE fellowship program, supported by the Zoological Society of London and Fondation Segré.