At EDGE we tend not to focus on a species’ extrinsic value as we feel that intrinsic value is not only more important, but also somewhat overlooked. Nonetheless in broader conservation terms, the justification of a conservation programme via highlighting ‘extrinsic values’ is unfortunately often a necessity for acquiring the green light.

For those of you unfamiliar with the term ‘extrinsic value, biologists use it to describe when an organism inadvertently provides or produces something that is beneficial to human wellbeing.

From the rainforests of Latin America acting as vast stores of carbon and regulating our climate, to the use of nematode worms as ‘model organisms’ whose study continues to further our understanding of genealogy, the natural world provides countless examples of species and even ecosystems with extrinsic value.

My view is that the ‘extrinsic value’ argument can and should be extended to embrace all life forms, and here I shall tell you why.

Firstly, extrinsic value is often indirect and can be very hard to identify in a complex ecosystem. With many hundreds of bacterial and fungal species alone thought to exist in any one square metre of soil, the potential number of interactions in an ecosystem is mind boggling. Furthermore, each such interaction has the potential to trigger minute changes to the surrounding environment. With the vast majority of bacterial organisms deemed undiscovered, it is impossible to state which communities are responsible for maintaining an ecosystem in a particular way, and indeed which organisms’ survival are mutually, dependent on the presence of other, perhaps larger life forms such as those in the EDGE scheme.

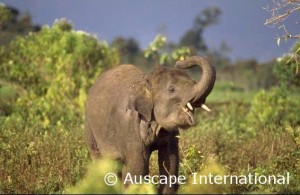

My point here is that even with extensive research, scientists do not fully understand how ecosystems function and which species are pivotal to habitat survival. For all we know any one of the species on our EDGE database may play a critical role in sustaining its surrounding environment. And some are already known to do so! From the Gilbert’s potoroo, whose feeding habits allow the dispersal of numerous important fungal species, to the Asian elephant, identified as a keystone species due to its manipulation of its natural environment, EDGE species of all sizes play important roles in ecosystem maintenance.

Regardless of a species known interactions, none whatsoever live in pure isolation. The loss of any biodiversity restricts the potential for cross species interactions, and this is known to weaken an ecosystem’s resilience to stress and change, making it susceptible to collapse.

Another argument relates to the use of model organisms. Studies of many animals, such as the nematodes mentioned above, have been instrumental in furthering scientific knowledge in a variety of fields. My argument here is that until we have sufficiently researched a species, we can not know whether it could be used as a model organism. This is no passing thought. Just last week a paper published in the journal Nature identified the first evidence of skin tissue regeneration in a mammalian species (African spiny mice). The authors here expressed their belief that further study of this organism may identify how to achieve similar results in humans. Publications such as this support my belief that there are many and more species that could be utilised as model organisms. This doesn’t mean I think we should go off and gather up rare species and put them in a lab. It means that we need to begin initiatives to boost endangered species populations to sustainable levels. This itself will require further research into species ecology and it may be here that an exciting discovery is made.

My final argument is a bit more light-hearted. Here my argument is that human cultures worldwide experience enjoyment and happiness when viewing the natural world. So what if one of our EDGE species is not proving to be a model organism or keystone species? Every day thousands of people worldwide pay to visit zoos, thereby applying extrinsic value to all of their inhabitants. Across the internet, millions of you will view amazing photos and videos, or read inspiring stories related to animals. These make you feel happy; they allow you to escape from reality for a few moments and they fascinate you. A wealth of scientific studies support the link between improved psychological wellbeing and experiencing nature in daily life. Indeed throughout history; cultures, works of art and legend have been inspired from natural encounters. If, in another 50 years, we lose this ‘unvaluable’ biodiversity around us, so we will restrict our own abilities to imagine, be inspired, and empathise with the figures and cultures from our own history.

So I’m not sure if I stuck to my original point, but I hope I have put across a reasonable argument as to why extrinsic value should not be the ultimate driver of conservation efforts. The simple reason is that we are not capable of determining ‘extrinsic value’ during the short time frames estimated before many of the worlds species become extinct.

Even if we were, the commercial view of ‘value’ is flawed. Investors want quick returns in profits or commodities they can sell. Tragically, this means that the long term value of ecosystem health and biodiversity is overlooked. These actions and views must change to embrace and sustain the innate value of our living world.