There is perhaps no better time than Black History Month to not only celebrate and highlight the amazing work of black conservationists, but also to reflect on the complexities of being a black person in modern conservation.

It can often feel impossible to escape the “whiteness” of western conservation policy, particularly as I type this as an employee of a ‘learned society’ established at the height of the British Empire. The current global conservation movement has its origins firmly rooted in western colonialism. The economic development of western states was—and continues to be—underpinned by the rapacious exploitation of natural resources far from home, with little to no thought for the impacts on the people and environment being exploited. Indeed, western society’s interest in conserving the natural world grew from concerns over the depletion of natural resources, such as ‘exotic’ wild animals hunted as game, which were previously considered to be limitless. The establishment of some of the world’s most iconic National Parks, such as Yellowstone and Yosemite, was accompanied by the forcible displacement of indigenous people and created a blueprint for conservation interventions worldwide. In fact, it wasn’t until 2007 that the rights of indigenous peoples to own and control their ancestral lands were recognised by the United Nations.

It is on these foundations that we now work to conserve the natural world, foundations built through exploitation and inequitable gains, in acute opposition to those who rely most on the natural resources we seek to protect. However, local and indigenous people are now rightly at the forefront of conservation efforts worldwide. The EDGE of Existence programme is not unique in its approach to conservation through the empowerment of local people to enact environmental change, working with young conservation leaders from nations that have suffered the most at the hands of western colonialism and capitalistic expansion.

To mark Black History Month 2020, several young conservation leaders from Africa, or of African descent, currently working with EDGE to conserve unique and threatened species, shared their perceptions of nature, conservation, and what it means to them to be black conservationists.

What does ‘nature’ mean to you?

Michele Marina Kameni Ngalieu, Cameroon: “Nature to me is liberty, diversity, wildlife, vegetation. It is the real meaning of life.”

Michael Akrasi, Ghana: “Nature means a lot of things to me: a source of food, clean water, air, and medicine. Nature is inspiration, serenity, wonder, happiness, beauty—just a few to mention. The world thrives on the wheels of nature, I believe. Nature is everything we see around us: plants, animals, mountains, rivers, streams, lakes, seas, oceans, forests, deserts. All the amazing things we take are provided for by nature. The next time you see magnificent mountains, nice blue oceans, thick rainforests, colourful butterflies, beautiful flowers and all the amazing plants and animals then know for surety that you have seen nature.”

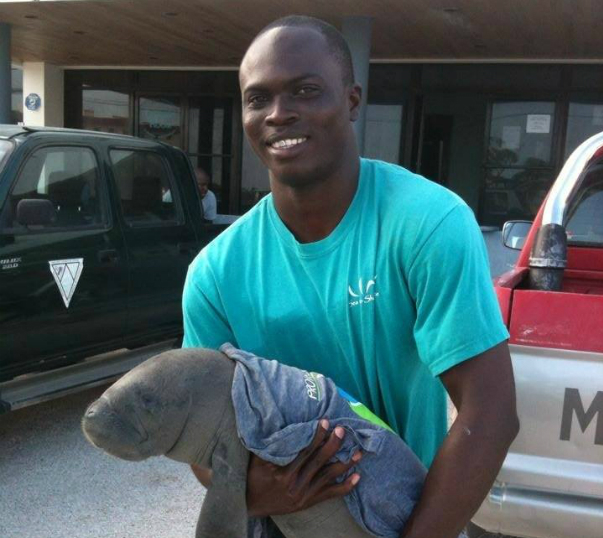

Jamal Galves, Belize: “The first word that comes to my mind is LIFE which is literally the most beautiful and fascinated thing on this planet.”

Who or what inspired you to pursue a life in conservation?

Kudzanai Dhliwayo, Zimbabwe: “From the time when I was young I have always been fascinated by animals and plants. I loved being outdoors and watching wildlife documentaries or reading magazines. My biggest inspiration has always been my Dad, contrary to everyone else he supported my hobbies and encouraged me to “go study something that has to do with animals, trees or the environment.” His exact words.”

Arnaud Tchassem, Cameroon: “Well, I have been interested in nature since my childhood, the way plants and animals interact. As I was growing, I came to realize that there are many living beings threatened. I therefore decided to make studying and protecting them my life’s work. This is more pertinent as, here in Africa, there is so much to be done and we are seriously lacking skilled personnel for this task.”

Rio Heriniaina, Madagascar: “I grew up with my grandfather who was a forest guard in countryside. He inspired me a lot to pursue my career in conservation. I still remember that every Saturday morning, we walked to the forest and he taught plant and animal identification.”

Jamal: “My grandmother inspired me. Though she did not quite understand the idea of conservation, she saw how passionate I was about manatees and allowed me as a young age to volunteer with researchers, and also encouraged me to follow that dream of mine. Though she did not quite understand our need to conserve nature, she did have an appreciation and love for the environment that rubbed off on me as well.”

What are the perceptions of conservation of those around you?

Emmanuel Amoah, Ghana: “The concept of conservation is still new to a lot of Ghanaians and mostly the rural poor see the idea as a luxury and foreign culture that hinders access to necessities for survival. Many people in Ghana, especially rural folk, see the idea of conserving wildlife—notably consumable ones—as a mere ‘academic nonsense’ and wonder why people will say wild animals should be protected. My family and friends have mixed feelings about my conservation work. While some see it as a new adventure and a good move to make an impact on the current and future generations, others think conservation work does not pay well and wish I could have taken up a lucrative profession in mining, law, and other much-respected professions in Ghana.”

Kudzanai: “Fortunately Zimbabwe is an environmentally conscious country as it is a signatory to many international conservation treaties or acts, e.g. CBD, CITES, CCD, UNFCC etc. However it is still a battlefield when it comes to implementing these legal frameworks, usually by the ordinary citizens, businesses and sometimes the government. My family and friends still do not understand what I do because to them a good profession is to be a medical doctor. Being in the field of ornithology is even more weird for them; they still do not see the need to have a person devoted to saving birds. To them birds are eaten or killed because they feed on our chickens or they are just ignored as the feathery winged things that fly around. Worse still, studying vultures it is particularly difficult for them to understand the importance of these majestic birds in our environment.”

Arnaud: “People are still very unaware of what conservation is all about. Most people still think that conservation is a waste of resources as many people are striving for a living on a daily basis with a lot of poverty around. Working for conservation should integrate such information to make it more acceptable and lasting.”

What challenges have you faced as a conservationist?

Jamal: “There is the misconception sometimes that conservation is not a field for African Americans like myself. Because of this we are not respected, we are underestimated, overlooked and unappreciated. At times this can have a significant impact on the important work we do.”

Rio: “There are several challenges that I have faced every day as conservationist. First, personal security. Some politicians and government representatives are not happy about my work, especially in mining areas where there are often conflicts. Then, the poverty and the level of education of the communities present a challenge because people are hungry, so they do not care about conserving a species.”

Michele: “As a young woman, it can be difficult to discuss my work with stakeholders, particularly village chiefs. I am not respected by some men and this can make my work difficult too.”

What does being a black conservationist mean to you?

Michael: “A recently published paper in Conservation Letters showed that 21-32 bird and 7-16 mammal species would have gone extinct without the conservation actions they received since the Convention of Biological Diversity came in to force in 1993. The tropics, of which Ghana is part, are wonderfully biodiverse. However, poverty is paramount amongst people living in the tropics, and this often leads to the exploitation of the diverse biodiversity in these regions. As a black conservationist, I feel proud that my work contributes towards maintaining the high biodiversity that exist within the tropics where I live.”

Arnaud: “Conservation is a life path that I have chosen, it is my job. I think I am out for that, and every step done toward the conservation of threatened biodiversity is worth doing to live in a more harmonious world. However, being a black conservationist is just a bigger challenge (maybe more than in other parts of the world); I believe that the basis of any conservation activity is people, their inclusion and their understanding of the merits projects through awareness raising.”

Rio: “Conservation is one of the best and advanced fields where there are people with widely diverse backgrounds, experiences and identities. This is inspiring. However, as a black conservationist I can see there are still gaps and imbalances between black conservationists and others because people of colour have long been excluded from environmental policy. Being a black conservationist is an honour but we need more black conservationists in conservation biology.”

Michele: “To be a black conservationist is to be someone who works hand-in-hand with local communities to contribute to preserving the environment, to help in the advancement of science and at the same time earning a living. But this work is not usually recognised nationally or internationally.”

Emmanuel: “To me, being a black conservationist is like a soldier accepting to be at the war front, you must be prepared for anything. I see myself as an adventurist who is determine to make history no matter the challenges. To me being a black conservationist is a very challenging profession that requires endurance and determination to cause change.”

Jamal: “It means everything to me being a black conservationist – a minority in a field dominated by other races. I extremely proud to represent and show that we too love this planet and are dedicated to saving it. I am, however, not fazed by it; the conservation work is too critical to be worrying about colour or race. We are one people living on one planet.”

Kudzanai: “Being a black conservationist means fighting for my heritage while being environmentally conscious. It is working towards saving wildlife, the wildlife which is/used to be so sacred to us, the black people. It is bridging the gap between indigenous knowledge systems and modern techniques that can help save the environment. It is having a people-centred approach which will make conservation accepted by my kin. It is understanding my culture and traditions and how they contribute(d) to conservation (which is amazing). And coming from a multicultural country, it gives me no greater joy to interact with people from different tribes and find out we all have conservation at the centre of our culture. However, it can be difficult sometimes to make people understand that we need to harvest in a sustainable manner just like our ancestors used to, in order to enjoy the benefits from our natural environment. By destroying the environment we are only making ourselves suffer, and the next generations too.”