The Erasmus Darwin Barlow Fund aims to give conservationists of the future new skills and experiences, by funding two places each year to join a ZSL EDGE of Existence expedition. The expeditions are named in tribute to the late Dr Erasmus Barlow, a Founder Fellow and key contributor to ZSL in his role as Secretary from 1980 to 1982.

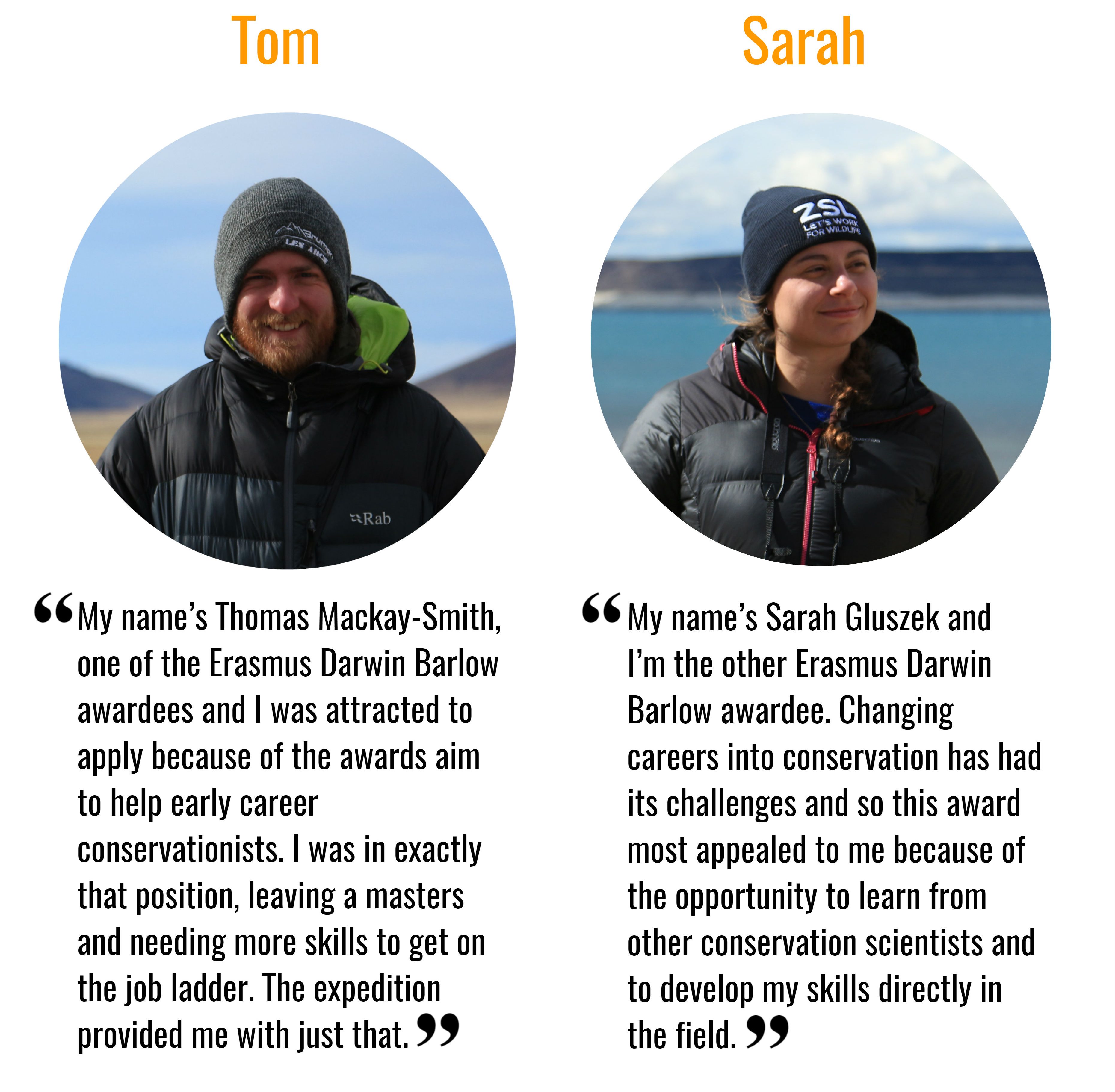

The two early-career conservationists chosen this year were Thomas Mackay-Smith (a Natural Sciences graduate from the University of Birmingham with an interest in conservation prioritisation tools) and Sarah Gluszek (who has used her background in Criminology to contribute to research in wildlife crime) who joined EDGE Conservation Biologist Claudia Gray to travel to one of the remotest regions of Patagonia, to research the mysterious Hooded Grebe.

Meet the EDBE awardees

The species

This year’s EDB expedition was centred around a fascinating, mysterious bird which lives in the remote Patagonian plateau lakes – the Hooded Grebe. The Hooded Grebe (Podiceps gallardoi) is a stunning, crimson eyed waterbird with an incredible head-bobbing mating dance. The species is endemic to Southern Patagonia and is listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN. The Hooded Grebe was only discovered in 1974, and since then the population has sadly dropped by as much as 95% in some areas.

The grebe captured the hearts of millions when a video clip of its iconic courtship dance went viral…it is quite an amazing spectacle!

Our goal

To date, the migratory route of the grebe is a mystery to scientists. The birds travel down from plateaus to spend the winter in coastal estuaries, but we have very little knowledge of where they go. Huge hydrodams are due to be built in this landscape over the next few years and we cannot effectively mitigate the impact of these dams if we do not know which parts of the landscape are important for the birds migration.

The aim of the expedition was to fit solar powered GPS loggers to the grebes, in an effort to obtain this information for the very first time. We had two models of lightweight GPS tags to test – this fieldwork was critical for determining which tag was most ergonomic for the birds and which one would reliably send back the most GPS data.

Arriving in Patagonia

Once we arrived in Patagonia we met Kini Roesler, an EDGE Affiliate who has been working for years to fill the knowledge gaps for the Hooded Grebe and develop a conservation management plan for the species. We also met Tomás, another Argentinean EDGE Fellow working on the El Rincon stream frog in Patagonia.

As soon as the team arrived in the remote Patagonian field station, the job over the first two days was to test the GPS tags and train the Hooded Grebe Project field staff in their use. Before we left for Patagonia, we attended a GPS tagging workshop at the ZSL offices in London. At the workshop we were able to test different GPS tagging brands and learn more about how they function, including the two that we were taking with us on the expedition: e-obs and technosmart.

The tags were tested using the radio transmitters over the hilly terrain around the field station, and all were working well. The field station staff picked up their use quickly, and this was vital so the data could be successfully retrieved later in the year when the EDGE team would not be there.

Once the field team were trained and the tags were tested, we began the difficult journey to a plateau called Buenos Aires, where there is a remote lake containing a large Hooded Grebe colony. We would be camping for 4 days to attach the tags to six birds and then time would be spent monitoring the birds, checking to see if their behaviour was normal following the tags being attached.

Tagging the grebes

The conditions on the plateaus are highly variable, and it is constantly windy! It is only possible to sail into the middle of the lake when the wind is low, so we had to wait until an evening with the right conditions. The tagging also had to be done at night, as the birds are less active and it was possible to shine a light onto the grebes, stunning them so they could be easily caught.

Luckily, the second evening on the lake was perfect. In a swift process a bird was caught, tags were tied and it was returned to the water in under 10 minutes. This was done for two birds on the first night, and four birds the following night.

We then spent the next three days monitoring the grebes with the tags on to make sure the tags were not disrupting their normal activity. We were concerned about one of the birds, who was acting increasingly distressed by the tag, so we removed it as to not harm the bird. One of the field technicians would be returning to the lake to add this last tag again and continue monitoring the birds. The other birds were not exhibiting any odd behaviour and seemed perfectly happy with the tags installed. After four days we left the lake to embark on the 10 hour, two day trip back to the field station.

Eradicating invasive mink

One important area of work by the Hooded Grebe Project is identifying and eradicating the predatory threat of the invasive American Mink (Neovison vison). Because of this, mink traps are set up in areas where their distribution overlaps with that of Hooded Grebe populations.

And so, in our second week of the expedition, we set off in pairs to check the conveniently-placed mink traps. We were given one transect each to check in our pairs, on which there was one mink trap placed every kilometer apart. The traps were positioned on the river, facing downstream. This way they would only target the minks who travelled along the rivers and therefore those that were a direct threat to the Hooded Grebe.

As the Patagonian terrain is not flat, progress was slow which meant a trap was checked approximately every hour. Checking each trap involved pulling the traps to the river bank and checking inside for a caught individual, and then replacing the bait with fresh meat slices and mink pheromones. It is rare to catch a mink in these traps, and this time no mink was caught.

Meeting with local researchers and community members

In our last few days, we took part in a knowledge exchange day with the fantastic researchers and volunteers at the field station. Setting up a projector in the common area, we waited for technicians from the other field station and local community members to arrive. With the wind blowing full force outside in a truly Patagonian way, we talked through our research projects and shared our experiences in IUCN Red Listing and social science research.

It was a great day of learning about one another’s work and our shared experiences. This was a wonderful opportunity to interact with the researchers at the Hooded Grebe Project and listen to the opinions of the local landowners. The afternoon was completed with a traditional Argentinian barbecue, roasting a whole mutton that had been donated by one of the neighbouring gauchos. We finished the night singing Argentine cumbia around the campfire, while grabbing guitars, buckets and shakers to provide accompanying acoustics.

Final words

One of the most valuable things we gained from the experience was being exposed to an exceedingly well-managed project. The Hooded Grebe project is a very successful field conservation programme which was started by only a couple of researchers over 15 years ago. Fast forward to the present, the team has a fully functioning research centre with over 100 volunteers visiting every year; and multiple PhD students are based at the centre.

Strong relationships with the local landowners were invaluable as most of the grebes are found on private land. Kini’s tiresome work integrating the project into the fabric of the local community impressed us greatly and seeing a project be so successful has really given us hope moving forward in our conservation careers.

Working with the scientists and Fellows from the EDGE of Existence programme meant that we were able to learn first-hand about the hard work and dedication involved in saving a single species. This opportunity allowed us to better understand the risks that species on the brink of extinction face. But it also gave us the chance to see one example of why EDGE species quintessentially should be saved. The Hooded Grebe is unique in its evolutionary lineage and social behaviour, and we were truly fortunate to have witnessed this incredible species in the wild.

Learn more about the Hooded Grebe expedition at our project page here.