As a crocodilian conservationist (yes, we exist!), I am often asked, “But what is the difference between a crocodile and an alligator?”, to which I usually respond, “Well, about 80 million years of evolution!”

By Phoebe Griffith

But what does 80 million years of evolution look like? Well, as humans, our nearest relatives who are about 80 million years removed are lemurs, so not all that closely related! Crocodilians – that’s the group made up of the crocodiles, alligators, caiman and gharials – all look fairly similar to us, because they share a similar ecological mode of life. Crocs are amphibious, spending most of their time in water, but basking and laying their eggs on land. They’re all predators, sharing a bone-plating of armoured scales, but all show great parental care and a range of acoustic communication. Those are the similarities. It’s not always been that way – fossil evidence reveals herbivorous crocodiles, marine crocodiles, galloping crocodiles running down their prey and even a tree-dwelling crocodile that overlapped in evolutionary time with humans. However, the amphibious-predator-superparent model is the norm for crocs in 2022.

Enough of the similarities. What we decided to research is the way that crocodilians are different. Because trust me, even to the untrained eye, some crocs look pretty weird. This is a Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) – more on them later. But check out that snout!

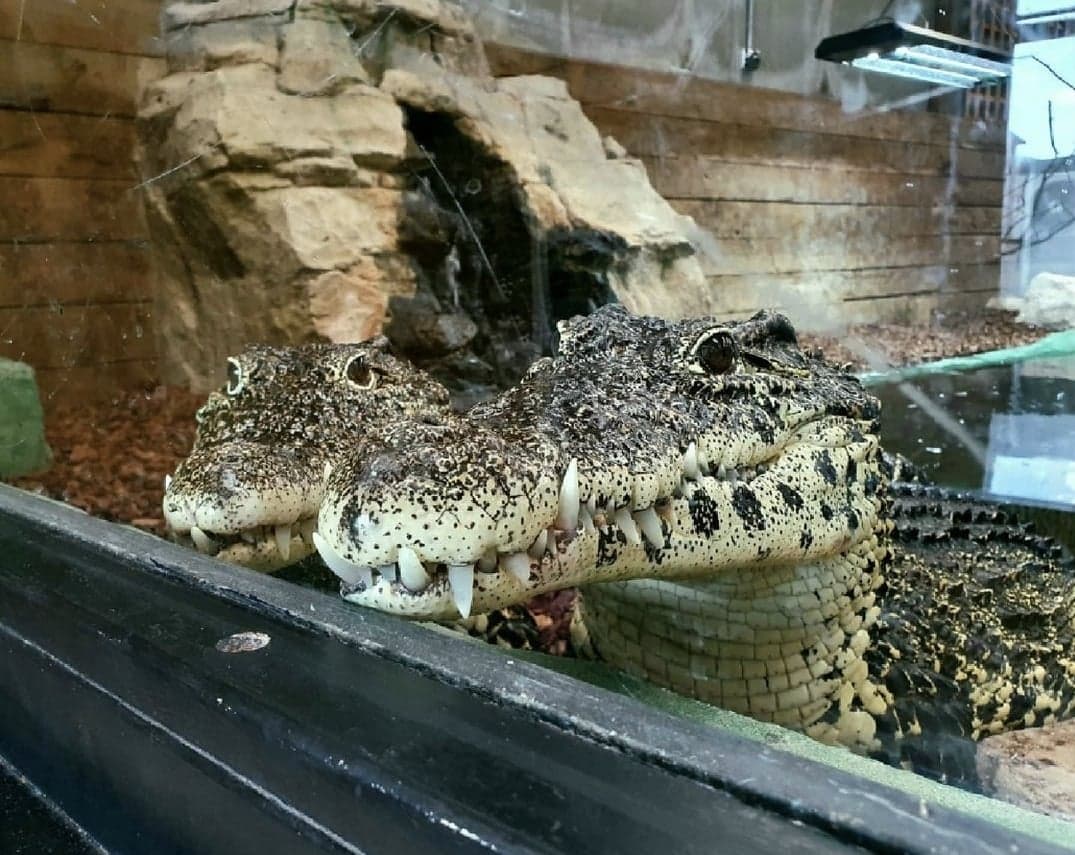

This is an adult African Dwarf Crocodile (Osteolaemus tetraspis). These guys are tiny. In fact, females can reach adult size at less than 1 metre in length. Contrast that with the famous Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) that can reach 7 metres long, and weigh well over a tonne.

Using a technique primarily developed by botanists, but increasingly used by animal ecologists and conservationists, we quantified the diversity of the ecological roles of crocodilians in our research published today in Functional Ecology. To do this, we created a database of ‘functional traits’ of all croc species, where functional traits are measurable characteristics that influence how species impact—and are impacted by—their ecosystem. For crocs we chose a wide range of traits, such as a measure of skull shape, maximum male size and female size at maturity, how specialist species are in their habitat requirements, and their ability to dig burrows (or not). We then looked at how similar these traits, and combinations of traits, are between species, and used this to quantify the ‘functional diversity’ of crocodilians.

What does being weird in some measurable characteristics tell us about croc ecology? Crocodilians that have unusual traits, or unusual combinations of traits, are likely to be performing unusual ecological roles, compared to other crocs. This allows us to quantify the most ‘functionally distinctive’ crocs – those species likely to have the most unusual, and therefore irreplaceable, ecological roles. This is a useful starting point for croc ecology because it is hard to study crocs in the wild – they’re amphibious, shy, cryptic, often live in inaccessible swamps, wetlands or rivers, and some species can be dangerous. Furthermore, many species are so endangered they’re found in very few places today, or in very low numbers. This makes it even more challenging to study what their role is in the environment, as many species, especially in Asia, are so rare that they are no longer at high enough densities to be performing their typical ecological functions (what we call ‘functionally extinct’).

Knowing how imperilled crocs are, we were interested in gauging how much of the functional diversity of crocodilians is likely to be lost under current extinction scenarios. Worryingly, we found that 38% of crocodilian functional diversity is likely to be lost, drastically reducing the diversity of ecological roles that crocodilians play globally.

To highlight those species that are most functionally distinctive – and also most threatened – for conservation action, we identified our top ‘EcoDGE’ (Ecologically Distinct and Globally Endangered) species as priorities for conservation. By conserving those most unusual species, we will capture a broader range of the ecological functions that today’s crocs represent. The top species that this analysis highlighted were the Gharial, Chinese Alligator (Alligator sinensis), Orinoco Crocodile (C. intermedius) and Cuban Crocodile (C. rhombifer) – species from the three main croc groupings (the gavialids, alligators, and two crocodiles, respectively). For those of you familiar with the EDGE Reptiles list, you’ll notice that the top two crocs here are the same as the top two EDGE crocs, which leads us on to the final analysis in our paper.

Since it is challenging to measure functional traits to calculate functional diversity (it requires a lot of field data, which is simply not available for many species) we investigated how well the EDGE metric performed at conserving the functional diversity of crocodilians. The EDGE metric aims to capture the diversity of the tree of life (phylogenetic diversity), in itself important for crocodilians as well, since 31% of the crocodilian tree of life is also projected to be lost under those same extinction scenarios. Although prioritising EDGE species isn’t designed to capture functional diversity, we found that conserving EDGE species in fact do did well at also capturing functional diversity. This was because many of the most functionally distinctive crocs were also the most evolutionary distinctive ones, with long periods of evolutionary isolation leading to unique ecological roles.

To show off some of the diversity of croc species that need conservation action, I have chosen my six-pack of top crocs. Well, seven, because we had a draw or – as we call it in evolution – convergence.

#1. The Gharial

Top of the Crocs, of course, we have our most functionally distinctive species, the gharial. These guys scored by far the highest in our distinctiveness rankings, and it is easy to see why. Gharial are–without doubt–the weirdest looking crocodilian. If you have never seen a gharial before, you’re probably wondering what is wrong with its nose. That lump on the end of the snout is called a ‘ghara’ and is only found in adult male gharial. Work by EDGE Fellow Jailabdeen suggests the lump is key for making a noise called a ‘pop’, which males use for flirting, fighting and chatting to their babies. Gharial are great parents, hence why this male has babies sitting on his head. What is even cooler is gharial aren’t just great parents to their own offspring – they lay eggs communally, then dominant males and females guard everyone’s babies in giant creches of up to 2,000 babies! ZSL EDGE Fellow Ranjana Bhatta has been documenting increasing levels of this creche guardian behaviour as the gharial population in Chitwan, Nepal, starts to recover.

However, despite their great parenting abilities, gharial are Critically Endangered. It doesn’t help them that they’re the most aquatic croc, only able to shuffle short distances overland, unlike other crocodilians which can lift their bodies off the ground and walk – sometimes distances of 10+ kilometres! This means when gharial’s riverine habitats have dams built across them, gharial populations get fragmented and often collapse. Furthermore, gharial have some of the most specific habitat requirements of any species, only living in open, sandy-banked rivers in South Asia. Their snaggled teeth make them especially at risk of getting accidentally entangled in fishing gear – especially gill nets. Mining of river sand for construction also means that gharial have fewer places left to nest. This loss of nesting habitat makes it even more exciting that EDGE Fellow Ashish Bashyal documented nesting in the Babai River of Nepal for the first time in 37 years. There’s hope for the gharial still!

#2+3. The other slender-snouted crocs

Next up, we have two surprisingly unrelated species, which share second place because they’ve convergently evolved both to be weird, and VERY hard to study. Second place goes to the West African Slender Snouted Crocodile (Mecistops cataphractus) and the Tomistoma (Tomistoma schlegelii).

Interestingly, because of the convergence of the two species, and the recent splitting of the West African Slender Snouted Crocodile and its closest relative, the Central African Slender Snouted Crocodile (M. leptorhynchus), into two separate species, they didn’t score very highly in our functional distinctiveness measures. However, they’re on my list because that fact alone is really interesting. The African Slender Snouted Crocs are crocodiles and Tomistoma are gavialids, and they are separated by around 60 million years of independent evolution, about the same distance as there is between humans and tarsiers (please google Tarsier if you haven’t seen one, you won’t regret it). Despite this, they have evolved to live a highly aquatic lifestyle in rainforest wetlands, rivers and swamps. Evolving to live in similar habitats and lead similar lifestyles has led to the species sharing similar traits, including small clutches of large eggs, a long yet robust skull, and a tendency to be tricky to study.

Tomistoma are the croc species we probably know the least about. What exactly do they eat? What is the species’ current distribution? How far do they move? How do they care for their babies? Everything about the Tomistoma is a mystery. What do we know? One thing that we are sure of is that this weird species is quietly disappearing from its swampy habitat. In fact, Tomistoma is about to be re-classified from Vulnerable to Endangered on the IUCN Red List, so the species could disappear before we get chance to answer these questions. Also today is August 5th – Happy World Tomistoma day!

The West African Slender Snouted Crocodile used to be just as under-researched, but that has been changing recently with awesome work by scientists in West Africa, such as EDGE fellows Emmanuel Amoah and Christine Kouman. Emmanuel, from Ghana, has identified key areas where this Critically Endangered species is still found, and is working with communities to protect and restore remaining habitat. Christine, from Cote d’Ivoire, is studying how the crocodile moves about its habitat and how it is impacted by people in its remaining protected strongholds.

#4. The mud dragon

Chinese Alligators are now found just in Anhui Province, but previously they were found throughout the Yangtze basin, and due to their cold tolerance were once found at the highest latitudes of any crocodilian species. Photo credit: Josh More/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 www.starmind.org

So far, our list of crocs has covered the three species with the longest, thinnest snouts, perhaps part of the reason they’re three species that aren’t known to dig their own burrows. People are often surprised to discover that most species of crocodilian are prolific burrowers. One of the species that digs particularly extensive burrow systems is the croc that comes second on our EcoDGE list, and top of the EDGE crocs list. The one and only ‘mud dragon’ or ‘扬子鳄’’, the Chinese Alligator. These dinky gators can reach adult size when just over 1 metre long, and they brumate (the gator version of hibernation) in their burrows to wait out winters in the Yangtze Basin. Most crocodilians are very vocal communicators, and the Chinese Alligator is an enthusiastic bellower, using a chorus of bellowing to communicate in the mating season. In fact, in some parts of China it is believed that the bellowing of the Chinese Alligator brings the rains.

Given that they live in one of the most human-impacted places on Earth, it is testament to the resilience of these mini gators that they are not yet extinct– but only just. Fewer than 100 individuals remain in the wild. Of the croc traits we measured, we also investigated which ones seem to confer resilience to extinction. We found that the ability to dig burrows and wait out periods of adverse weather is one of characteristics of croc species that makes them less likely to be threatened with extinction, as is the ability of crocs to ‘aestivate’, that is a behavioural dormancy to cope with periods of dry weather. Most importantly, crocodilians that invest more in reproduction, and are generalists in their habitat requirements, are also less likely to be threatened. However, when human pressures get too much even the toughest mini gators will struggle – we found Asia in particular was the continent with the greatest human impact within croc distributions, leading to most populations of crocs in Asia being threatened with extinction.

#5. The Cuban Crocodile

Despite Asia being a hotspot of threatened crocs, the most range-restricted croc is in fact found in the Caribbean. A crocodile that hunts on land, in groups, and can even jump to pick prey out of trees… the subject of a B-list horror movie, right? Nope – it is the resident of Zapata Swamp in Cuba, the only place in the world where the Cuban Crocodile is still found. Cuban Crocodiles are famous for being really clever, and very capable at moving and hunting on land. In the Cuban Archipelago, whilst the Cuban Croc was evolving, there were no large terrestrial predators, so it is possible that the Cuban Croc evolved to be such a terrestrial species to fill that niche. Although other croc species can be very terrestrial – notably the Dwarf Caimans and African Dwarf Crocodiles – the big difference is given away by their names. Those other species are very small, whilst the Cuban Crocodiles historically could reach 5 metres, although these days individuals as large as that are no longer seen.

#6. Buwaya

The other species of crocodile endemic to islands of a single country is the Philippines Crocodile, or Buwaya (C. mindorensis), which our analysis identified as a species which shares a lot of similarities with the Cuban Croc, perhaps owing to their island evolution. The Philippines Crocodile is a friend to farmers. Work by Joey Brown and colleagues has found that Philippines Crocodiles eat invasive Golden Apple Snails, a major agricultural pest in the country. In fact, snails are a major dietary component of many croc species. Despite the fearsome reputation of species like Nile Crocodiles (C. niloticus) and Saltwater Crocodiles for taking large terrestrial prey such as wildebeest and deer, most croc diets feature far smaller prey. Crocodiles primarily eat aquatic animals like fishes, crustaceans and other invertebrates including snails and other molluscs, supplemented in larger individuals by terrestrial prey including birds and mammals. Given that crocodiles have two skeletons – their inner skeleton and outer osteoderms – and that females lay calcified eggs, it probably makes sense that crocs tuck into so many crunchy prey items with calcified shells like crabs, crayfish, snails and mussels.

#7. American Crocodile

So, the Saltwater Crocodile came in at number 2 on our list of functionally distinctive crocs, and the saltwater crocodile does deserve that place. It’s the biggest, baddest, longest-distance-voyaging croc of the lot. However, it is missing out to the American Crocodile which is also immensely cool, and is perhaps even more saltwatery than the saltwater crocodile, so it’s made my list instead. The American Crocodile’s scientific name – Crocodylus acutus (pronounced ‘a-cute-us’) literally has cute in the name, so it’s easy to realise they’re much less ferocious than their scaly saltwater cousins in the Indo-Pacific. The American Crocodile is a species who looooves a beach in the Caribbean as much as the next person. This ocean-going croc is super tolerant of saltwater, but in fact all ‘true crocodiles’ have a special gland on their tongue for dealing with life in salt water. This lingual salt gland excretes excess salt that builds up in the crocodile’s body whilst living life at sea, enabling them to live and feed in saltwater. Since tomorrow is Jamaican Independence Day, I want to mention the ‘Jam Crocs’ – the American Crocodiles found in Jamaica. Jamaican Crocodiles highlight some of the issues most croc species face. In particular, a major threat is habitat loss due to development for housing, hotels and roads, so often right on the riverbank and coastal habitats that crocs use for basking and nesting. Habitat loss can lead to crocodiles shifting to live very close to people, which means education is key so people can live safely alongside them. Awesome work by croc conservationist Treya Picking highlights the importance of community conservation so that people know how to live safely alongside crocodiles (for example, by not feeding them), and so wildlife rangers can move crocs that get lost in human settlements.

Crocodilian diversity is at huge risk if we don’t act now to save these unique and often bizarre species. I know I am one of many who would find the world less fascinating if they disappeared, but this study also highlights how much more than just species stand to be lost: the ecological roles of species in their ecosystems can be lost too. Since we have only just started trying to investigate these roles, we can’t predict what knock-on impacts the losses of certain crocs will have in the freshwater systems they live in. This is particularly worrying, as freshwater systems are some of the most important on earth for both biodiversity and human health and wellbeing. Conservation of these species and their habitats requires action now, by all of us, to prioritise and protect them. By conserving unusual but functionally important species such as the Gharial, Chinese Alligator or Philippines Crocodile, we are taking a step towards conserving the diversity of life, and all of us who rely on it.

Phoebe Griffith is a PhD student with the University of Oxford’s WildCRU and ZSL’s Institute of Zoology.

Related blog posts

EDGE of Existence launches the EDGE Reptile list

Turtles that breathe through their genitals and chameleons the size of a human thumbnail are amongst the weird and wonderful reptiles heading for extinction unless urgent action is taken, according to the new EDGE Reptile list released by the ZSL EDGE of Existence programme.

My work with the slender-snouted crocodile – by Segré EDGE Fellow Emmanuel Amoah

I have always had the burning desire to contribute significantly towards biodiversity conservation. However, in conservation, both passion and competency must go hand-in-hand to…

In search of the world’s least-known crocodile

The morning had been a blur of breakfast, last minute packing and passport checks, so it wasn’t until my tube finally trundled into Heathrow…